Music theory unveils the “secret sauce” behind captivating music, exploring elements like rhythm and harmony; it’s a fundamental guide for musicians of all levels.

Understanding these concepts enhances appreciation and unlocks creative potential, offering a deeper connection to the art form itself.

What is Music Theory?

Music theory isn’t a rigid set of rules, but rather a framework for understanding how music works. It’s the study of the practices and possibilities of music, analyzing the elements – rhythm, melody, harmony – and their relationships.

Essentially, it’s a language that allows musicians to communicate effectively about music, dissecting compositions and predicting how sounds will interact. It provides tools to describe musical structures, from simple chord progressions to complex orchestrations.

This knowledge isn’t about stifling creativity, but empowering it; it’s about understanding the “why” behind the music, allowing for informed and intentional artistic choices. It’s the foundation for composition, improvisation, and analysis.

Why Learn Music Theory?

Learning music theory unlocks a deeper appreciation for the music you love, moving beyond simply enjoying sounds to understanding their construction. It empowers you to analyze songs, identify patterns, and comprehend the composer’s intent.

For musicians, it’s invaluable. It facilitates songwriting, improvisation, and arranging, providing a vocabulary to articulate musical ideas and collaborate effectively. It also aids in ear training, improving your ability to recognize intervals, chords, and melodies.

Ultimately, music theory isn’t just academic; it’s a practical tool that enhances musicality, fosters creativity, and opens doors to a richer, more informed musical experience.

Basic Elements of Music

Music fundamentally comprises rhythm, melody, and harmony—intertwined elements creating structure and expression. These building blocks form the foundation for musical composition and analysis.

Rhythm and Meter

Rhythm is the heartbeat of music, governing the duration of notes and silences. It’s the arrangement of sounds in time, creating patterns that drive the music forward. Meter organizes these rhythms into recurring groupings, or beats, establishing a predictable pulse.

Understanding time signatures is crucial; they indicate how many beats are in each measure and what kind of note receives one beat. For example, 4/4 time signifies four quarter notes per measure.

Note values – whole, half, quarter, eighth, and sixteenth notes – determine how long each note is held, influencing the overall rhythmic feel. Duration is relative, creating complex and engaging rhythmic textures. Mastering these basics unlocks a deeper comprehension of musical structure.

Time Signatures

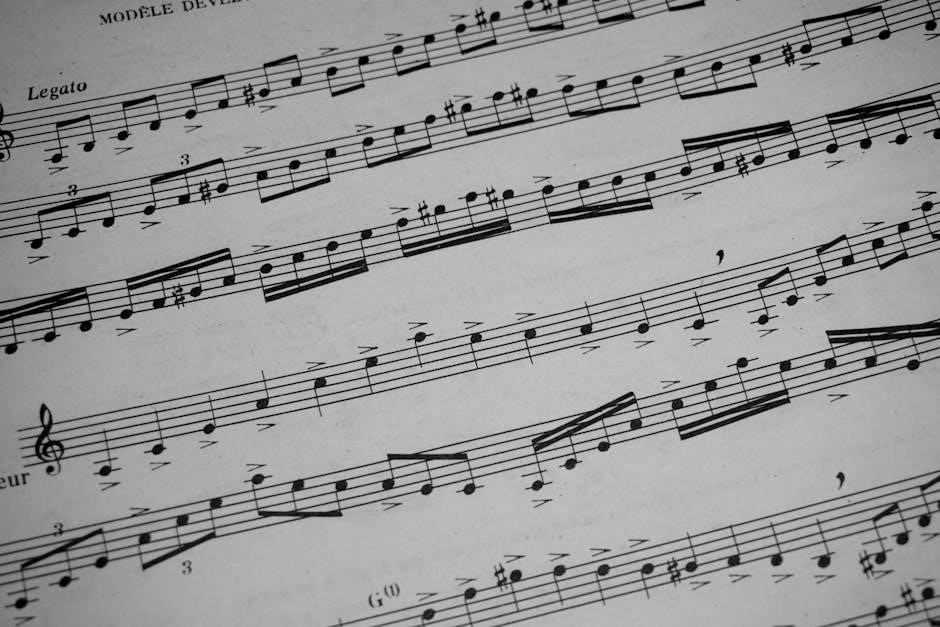

Time signatures are foundational to understanding rhythm, appearing at the beginning of a musical piece. They’re represented by two numbers, one stacked on top of the other, resembling a fraction; The top number indicates the number of beats in each measure, while the bottom number defines the note value that receives one beat.

Common time signatures include 4/4 (four quarter notes per measure), 3/4 (three quarter notes), and 6/8 (six eighth notes). These dictate the rhythmic framework. Recognizing time signatures allows musicians to accurately interpret and perform a piece, grasping its underlying pulse and structure.

Changes in time signature within a piece create rhythmic variation and interest.

Note Values and Duration

Note values determine how long a note is held, directly impacting rhythm. The whole note receives four beats in 4/4 time, the half note receives two, the quarter note receives one, and so on. Each note value has a corresponding rest, indicating silence for the same duration.

Eighth notes, sixteenth notes, and beyond further subdivide the beat, creating more complex rhythmic patterns. Dots placed after a note increase its duration by half its original value. Understanding these values is crucial for accurate timing and rhythmic interpretation.

Precise duration creates musical phrasing and groove.

Melody and Pitch

Melody, the linear succession of musical tones, is the memorable part of a song. Pitch refers to how high or low a note sounds, determined by its frequency. The foundation of pitch lies within the musical alphabet – A, B, C, D, E, F, and G – which repeats across octaves.

These notes are organized into scales, providing the building blocks for melodies. Key signatures indicate which notes are sharp or flat throughout a piece, defining the tonal center. Major scales sound bright and happy, while minor scales often convey a more somber mood.

Melodic contour and intervallic relationships create musical expression.

The Musical Alphabet

The musical alphabet consists of seven natural notes: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. After G, the sequence repeats, starting again with A in the next higher or lower octave. These letters represent specific pitches, forming the basis for all melodic and harmonic structures.

Sharps (#) raise a note’s pitch by a half step, while flats (♭) lower it. These alterations expand the available pitches beyond the seven natural notes. Understanding the order and relationships between these notes is crucial for reading music and comprehending musical intervals.

The alphabet provides a foundational framework for constructing scales and chords.

Scales and Key Signatures

Scales are a series of notes arranged in a specific order, defining a key. Major and minor scales are the most common, each creating a distinct emotional character. Key signatures indicate which notes are consistently sharp or flat throughout a piece, simplifying notation.

A key signature appears at the beginning of the staff, showing the altered notes. These alterations are derived from the scale of the key. For example, the key of G major has one sharp (F#), indicated in its key signature.

Understanding scales and key signatures is vital for composing, improvising, and analyzing music.

Harmony and Chords

Harmony explores how notes combine simultaneously, creating chords and progressions. Chords are built by stacking notes, typically in intervals of thirds. A triad, the most basic chord, consists of three notes: a root, a third, and a fifth.

Different chord qualities – major, minor, diminished, and augmented – evoke varied emotions. Chord progressions are sequences of chords that create musical movement and structure. Common progressions, like I-IV-V-I, form the foundation of countless songs.

Understanding harmony allows musicians to create rich, layered textures and compelling musical narratives.

Chord Construction

Chord construction begins with a root note, establishing the chord’s tonal center. Typically, chords are built using intervals of thirds stacked upon this root. A major chord consists of a root, a major third, and a perfect fifth. Conversely, a minor chord utilizes a root, a minor third, and a perfect fifth.

Adding further intervals creates more complex chords. Diminished and augmented chords introduce altered thirds and fifths, adding tension and color. Seventh chords add a seventh interval above the root, enriching the harmonic texture.

Understanding these building blocks is crucial for analyzing and composing music.

Chord Progressions

Chord progressions are the sequence of chords used in a piece of music, forming the harmonic foundation. Common progressions, like the I-IV-V-I in major keys, create a sense of resolution and familiarity. These progressions utilize the relationships between chords within a key.

Movement between chords creates tension and release, driving the music forward. Analyzing progressions reveals how composers establish mood and structure. Variations on standard progressions, incorporating borrowed chords or altered harmonies, add complexity and interest.

Understanding chord progressions is vital for both composing and improvising, allowing musicians to create compelling harmonic journeys.

Understanding Intervals

Intervals define the distance between two pitches, categorized by number and quality—major, minor, perfect, augmented, or diminished—forming the building blocks of harmony.

Types of Intervals

Intervals are fundamentally classified by their numerical size, representing the ‘distance’ between two notes. A second is the smallest interval (like C to D), while a ninth represents almost an octave leap. These numbers indicate the scale degree difference.

Beyond numerical size, intervals are categorized as melodic (played sequentially) or harmonic (played simultaneously). Further defining them are qualities: major, minor, perfect, augmented, and diminished. Perfect intervals (unison, fourth, fifth, octave) are stable and foundational. Major and minor intervals create color and tension. Augmented and diminished intervals add dissonance and complexity.

Recognizing these interval types is crucial for understanding chord construction, melody creation, and harmonic progressions, forming the basis of musical analysis and composition.

Interval Quality

Interval quality refines the character of an interval beyond its numerical size, adding nuance to its sound. Perfect intervals – unison, fourth, fifth, and octave – possess a stable, consonant quality, forming foundational harmonic relationships. These are largely unaffected by alterations.

Major and minor intervals introduce color and emotional depth. Major intervals sound brighter and more assertive, while minor intervals evoke a sense of sadness or introspection. Augmented and diminished intervals create tension and instability, often used for dramatic effect.

Determining quality involves comparing the interval to its major or perfect counterpart; alterations (sharps or flats) define whether it’s augmented, diminished, or remains major/minor.

Key Signatures and the Circle of Fifths

Key signatures and the Circle of Fifths reveal relationships between keys, showcasing sharps or flats and aiding in understanding harmonic progressions and modulations.

Major and Minor Keys

Major keys generally evoke feelings of happiness and stability, built upon a major scale structure with a characteristic bright sound. They possess a distinct quality often associated with resolution and optimism in musical expression.

Conversely, minor keys often convey emotions like sadness, melancholy, or tension, stemming from their minor scale structure. These keys offer a different harmonic palette, creating a more introspective or dramatic atmosphere.

The difference lies in the intervals within the scale; a minor key features a lowered third degree compared to its relative major. Understanding this distinction is crucial for analyzing and composing music, as it fundamentally shapes the emotional impact and overall character of a piece. Recognizing these key qualities enhances musical interpretation.

The Circle of Fifths Explained

The Circle of Fifths is a visual representation of the relationships between keys, organized by perfect fifths. Moving clockwise increases by a fifth (e.g., C to G), adding a sharp to the key signature. Conversely, counter-clockwise decreases by a fifth (C to F), adding a flat.

This circle demonstrates how closely related keys share common tones, aiding in smooth chord progressions and modulations. It’s invaluable for understanding key signatures, harmonic function, and composing music.

The circle also illustrates the relationship between major and minor keys; each major key has a relative minor key located three semitones below it. Mastering the Circle of Fifths unlocks a deeper understanding of tonal harmony and musical structure.

Chord Voicings and Inversions

Chord voicings alter note arrangement for varied textures, while inversions change the bass note, creating harmonic interest and smoother transitions between chords.

Basic Chord Voicings

Chord voicings fundamentally impact a chord’s sonic texture, moving beyond simply playing the root, third, and fifth. A ‘close voicing’ keeps these notes tightly packed together, creating a compact sound often used in simpler arrangements. Conversely, ‘open voicings’ spread the notes across a wider range, resulting in a more spacious and airy feel.

Experimenting with note order within the chord – for example, placing the fifth in the bass instead of the root – subtly alters the harmonic color. Different voicings can emphasize different aspects of the chord, making it sound brighter, darker, or more complex. Mastering basic voicings provides a foundation for more advanced harmonic exploration and arrangement techniques, offering near-endless possibilities.

Chord Inversions and Their Use

Chord inversions rearrange the notes of a chord, placing a note other than the root in the bass. A first inversion has the third in the bass, while a second inversion places the fifth. This alters the chord’s sound and function within a progression.

Inversions create smoother bass lines, facilitating seamless transitions between chords. They also add harmonic interest and can subtly change the emotional impact of a progression. Utilizing inversions avoids large leaps in the bass, resulting in a more flowing and connected sound. Understanding inversions is crucial for effective voice leading and crafting sophisticated harmonic arrangements, offering a wider palette of sonic textures.

Musical Form and Structure

Musical form defines a composition’s overall plan, utilizing structures like verse-chorus or more complex arrangements to organize musical ideas effectively.

Analyzing structure reveals how sections interact, creating a cohesive and engaging listening experience.

Common Musical Forms (e.g., Verse-Chorus)

Verse-chorus form is arguably the most prevalent in popular music, offering a balance of lyrical development and memorable repetition. Verses typically advance the narrative or explore different facets of a theme, while the chorus provides a recurring, catchy melodic and lyrical anchor.

Other common forms include ABA (ternary form), where a central contrasting section (B) is framed by repetitions of an initial section (A), and sonata form, frequently used in classical music, featuring exposition, development, and recapitulation.

Understanding these structures allows musicians to both analyze existing pieces and construct their own compositions with intentionality, creating a satisfying and predictable, yet engaging, listening experience for the audience.

Analyzing Musical Structure

Analyzing musical structure involves dissecting a composition to understand how its elements – melody, harmony, rhythm, and form – interact. Begin by identifying repeating sections, like verses and choruses, and noting their variations.

Pay attention to transitions between sections, observing how the music builds tension or releases it. Charting chord progressions reveals harmonic patterns, while rhythmic analysis highlights recurring motifs and syncopation.

This process isn’t merely academic; it deepens appreciation and provides insights into the composer’s intent. Recognizing structural elements empowers musicians to deconstruct, reimagine, and ultimately, create their own compelling musical narratives.

Advanced Concepts

Advanced music theory delves into modes, modal interchange, and non-harmonic tones, expanding harmonic palettes and offering nuanced compositional possibilities for skilled musicians.

Modes and Modal Interchange

Modes, variations of scales, offer distinct melodic characters beyond major and minor, each evoking unique emotional qualities. These ancient scales, like Dorian and Phrygian, provide composers with fresh sonic landscapes.

Modal interchange involves borrowing chords from parallel modes (e.g., borrowing from a parallel minor key while in major). This technique adds harmonic color and surprise, enriching chord progressions with unexpected twists.

Understanding modes and interchange allows musicians to move beyond conventional harmony, creating more sophisticated and expressive compositions. Experimentation with these concepts unlocks a wider range of emotional depth and stylistic possibilities, fostering originality and artistic growth.

It’s a powerful tool for adding nuance and complexity to your music.

Non-Harmonic Tones

Non-harmonic tones are notes that don’t neatly fit within the underlying chord structure, adding melodic interest and tension. These “passing tones,” “neighbor tones,” and “suspensions” create movement and color, resolving to chord tones for a satisfying effect.

They function as embellishments, momentarily disrupting the harmonic flow before returning to stability. Skilled use of non-harmonic tones elevates melodies, preventing them from sounding static or predictable.

Understanding their proper resolution is crucial for creating smooth and expressive musical lines. Mastering these techniques allows composers to craft more nuanced and emotionally resonant pieces, adding depth and sophistication to their harmonic language.

They are essential for expressive melodic writing.